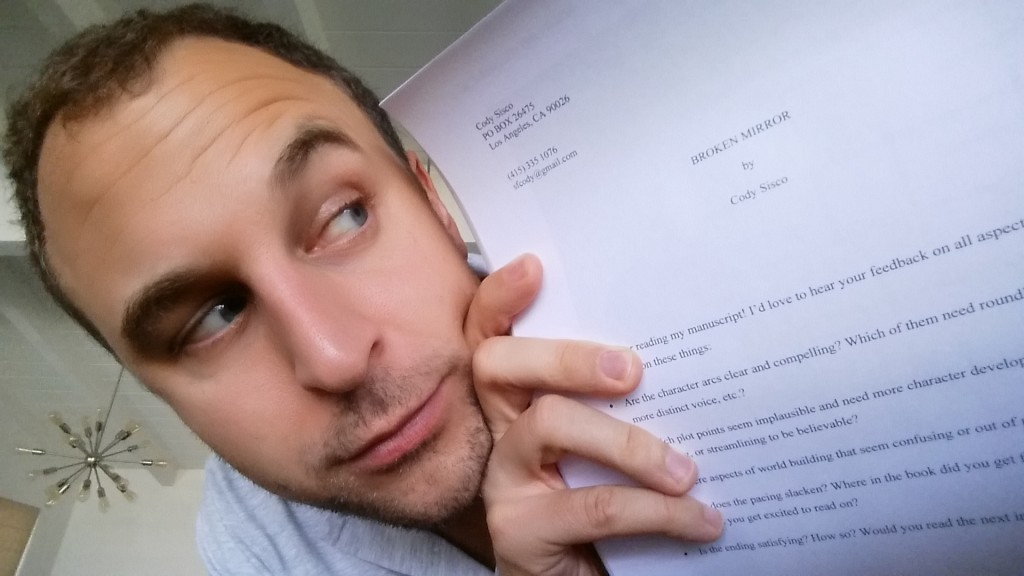

I’m making one final editing pass for Broken Mirror before sending the manuscript to my beta readers. The focus will be on deepening characterization, cleaning up any plot holes introduced during the previous edit, and proofreading for typos, punctuation mistakes, etc.

Before diving in, however, I’m looking for inspiration to help me get into the right mindset. I want to re-imagine how Victor Eastmore’s mental disorder manifests itself and how I can convey that through language. I want readers to share in his experience, to come away from the book feeling like they’ve gained an understanding of how he perceives the world and his place in it.

I’ve written before about my inspiration for writing the Broken Mirror series. Now I want to share how I look for inspiration when editing.

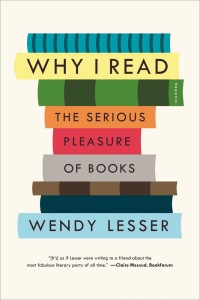

I received a hard copy of Wendy Lesser’s “Why I Read” as a gift at least one year ago, but I held off reading it, mainly because it seemed like one of those books that needs the right moment to have an impact. I was right; reading her wide-ranging thoughts on literature has giving me many ideas for revising the manuscript. Last night, as I read her insights on Henry James, Dostoyevsky, and Asimov, several things occurred to me:

The strength of any book relies mainly on the memorability of its characters and how they solve the problems inherent in the premise. For Broken Mirror, this means I need to strengthen passages that describe how Victor manages his mental disorder (through herbalism, behavioral therapy, and brainhacking, for example). But it’s not enough to include these passages. They have to seem important (emotionally) as well as pivotal to the progression of the plot. I now have a better idea where I’ll focus my editing energy and my approach to those sections of the book.

Language at the line level, i.e. the vocabulary, grammar, and cadence of individual sentences, must feel persuasive and cohesive throughout the entire novel. This is an important point to remember as I’m facing literally hundreds of pages and may be tempted to rush through, thinking, “Oh, that’s good enough,” or “I’m the only one who knows what’s wrong with that bit of dialogue.” No, every sentence is important, or it gets cut.

There are many very sophisticated readers out there, and I hope they will enjoy my book, that they’ll think it’s meaty, complex, and innovative enough for them to appreciate as a literary work. At the same time, there are many readers looking to be entertained by a mainstreamish, cyberpunk, alternate reality, detective sci-fi epic. These are not mutually exclusive audiences–my goal is to appeal to both, which means I must write and edit at multiple levels, using every technique I have at my disposal, and some that I haven’t quite mastered yet. So I’ll pay attention to the language, but I need to remember just to tell a good story.

After finishing Why I Read, I wanted to read ALL THE BOOKS, especially those that Wendy’s descriptions brought to life. However, I got into a bit of a funk by trying to fall in love with the wrong authors.

Based on an io9 list of science fiction and fantasy classics, Dahlgren by Samuel Delany had come to reside on my Kindle, and I had come to believe it was an important book for me to read. A few months ago, I read the first chapter in a bit of a stunned daze, (Could this actually be the final, edited, published version and not some rough, hastily composed early draft?). After the first chapter, I put the book down, both figuratively and literally, and didn’t come back to it.

But last night, seeking inspiration, I thought, I’ll give Dahlgren another try, all the way to the end, so that its literary majesty can soak into my brain and improve my writing. I made it to Chapter 4. There was no character, no plot, no feeling to hook me–the book was all shiny surfaces and writerly flourishes and it failed on a basic level to engage me. Perhaps if I approached it as an extended prose poem… No, I would only be fooling myself. Despite the appeal of setting and erotica, there were too many broken and misshapen images, too much tortured grammar, too many hideously generic lines of dialogue. Dahlgren may be a deliberate metafictional tour-de-force that Delany meticulously crafted, but it wasn’t for me. China Miéville writes using similarly lush, complex language and, perhaps, includes even more provocative settings with a better (though not outstanding) grasp of narrative drive. Anyway, I stopped reading, feeling guilty until I read the 1-star reviews at Goodreads and was reassured that many saavy readers had similar feelings and were able to express them far more eloquently their distaste.

But my book-reading fail-streak continued. I tried starting Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series and The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks, but they didn’t hook me right away–I plan to return to both when my patience is rejuvenated.

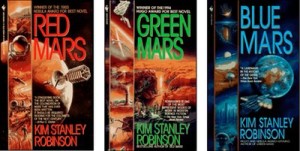

Then I picked up a slim volume containing a few of Kim Stanley Robinson’s short stories. To my utter dismay, after I started reading “The Lucky Strike,” two pages in, I didn’t seem to be interested. This is an author who I’ve followed very closely since discovering Red Mars when it was published and waiting patiently for years for the sequels, Green Mars and Blue Mars.

His more recent works also continue to impress me, and I’m waiting to read his most recent, Aurora, for when I need a really good book. It was, therefore, shocking that “The Lucky Strike” didn’t appeal. (Note: I much prefer longer fiction over short stories, but I’m reasonably certain that I wouldn’t have been able to tell the length of “The Lucky Strike” by reading the first few pages, and I don’t think it influenced my initial opinion.)

I went to sleep disappointed. This morning, I gave “The Lucky Strike another shot.” I made it to page 26, settling into the story this time, certain I would make it to the end. And then I encountered several lines that impressed me so much, that created such useful openings into my editing process, that I had to stop reading and share them with you.

A little bit of setup (and spoilery!) is required.

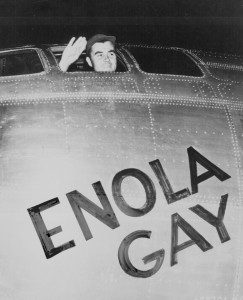

In this alternate history story, the Enola Gay (the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber responsible for the horror of Hiroshima), crashes on a training run, killing the pilot and crew. As a result, the story’s protagonist, Captain January, is slotted to drop the bomb using another bomber, the Lucky Strike, to fulfill the Enola Gay‘s mission. We become keenly aware of Captain January’s anxiety when he’s shown what kind of payload he’s dropping–he and the rest of the crew watch a film of the Trinity test explosion’s atomic fireball blossoming in the desert. Interesting setup, right?

Here are the lines that caught my attention:

For months now he [January] had been sure he would never fly a strike. The dislike Tibbets and he had exchanged in their looks (January was acutely aware of looks) had been real and strong.

…

Back on Tinian the lieutenant colonel congratulated them and shook each of their hands. January smiled with the rest, palms cool, heart steady. It was as if his body were a shell, something he could manipulate from without, like a bombsight.

…

With a rush of smoke out of him January realized how painfully easy it was to fool someone if you wanted to. All action was no more than a mask that could be perfectly manipulated from somewhere else.

First, I love how January’s sensitivity to the opinions of others is given physical form in the line, “January was acutely aware of looks.” And then it continues, “January smiled with the rest” [emphasis mine, here we see January aware that other people are smiling], and how easy it is, he thinks, to fool people. But we are not fooled. We know how much he is bothered about the bomb he must drop on Hiroshima. The difference between what he feels, what he shows to others, and what he will do about it is the hook.

Second, Robinson–Isn’t it strange how I feel I have to refer to Wendy Lesser by her first name because her book felt so intimate that I can’t imagine calling her “Lesser;” yet I can’t call my favorite author, “Kim,” even though I know his writing well?–anyway, Robinson uses metaphorical language that seems so effortless, so exactly on point that I had to put the book down and just breathe. January becomes his role. He becomes the bombsight. He reassures himself that action is just manipulation from without, even if “without” represents his conscious mind. The effect of this language is paradoxical. He becomes the thing that bothers him–the bomb–while at the same time distancing himself from the act–he can be “manipulated from somewhere else.” It sounds easy, uncomplicated, and the right frame of mind for distancing himself in advance from the atrocity that he is about to commit. This is genius because it creates tension at exactly the crux of the story: he is about to drop a bomb on Hiroshima and feels bad about it, but cares too much what other people think to raise any objection! So he says, “Yes, sir,” to his commander, he says, “Don’t worry about me,” to the military psychiatrist, and it appears as if he will indeed drop the bomb. And we’ll keep reading to find out if he does.

I’m now going to finish the story, and thanks to Robinson’s clever, emotionally rich writing, I won’t be able to stop until I reach the end.